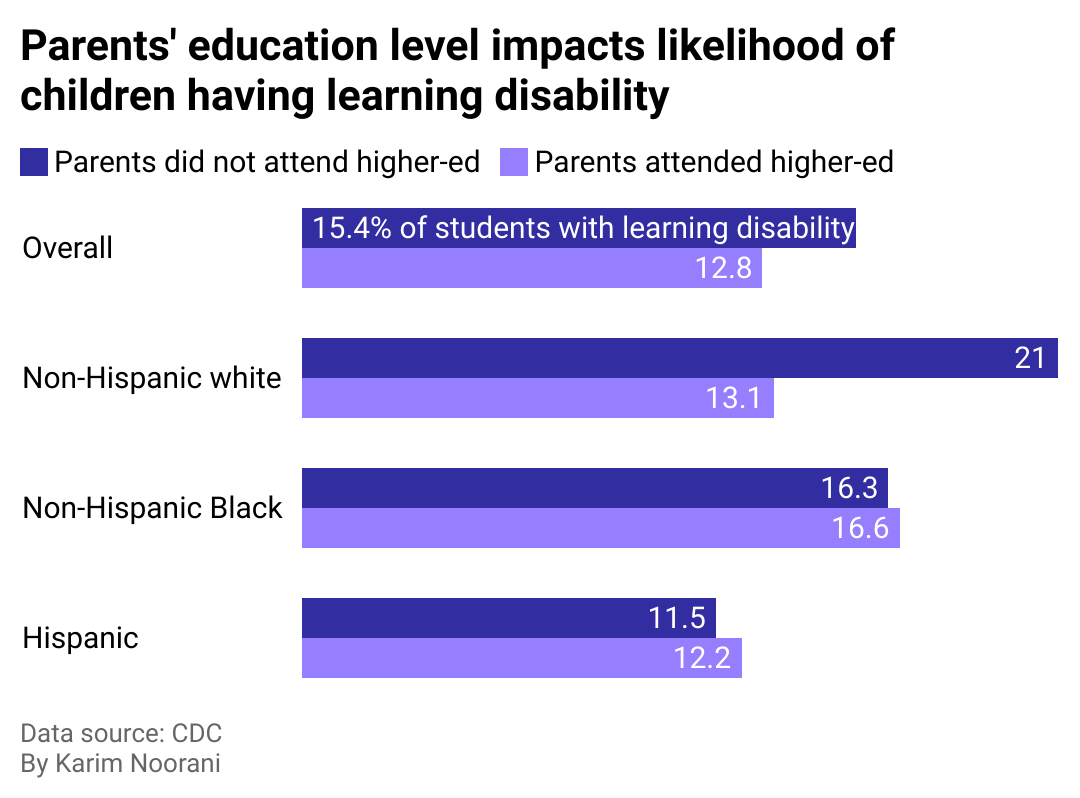

New Africa // Shutterstock No two children with learning disabilities are the same. They’ll have different family situations, academic needs, and backgrounds. In public schools, however, children with learning disabilities need an educational or medical diagnosis to get in-school support. Between 2021 and 2022, 7.3 million American students between the ages of 3 and 21 received special education and related services for disabilities recognized under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. This number is equivalent to 15% of all U.S. public school students. The most common group of students receiving special education services were those experiencing “specific learning disabilities,” according to the National Center for Education Statistics, comprising approximately 1 in 3 pupils receiving special education services during that time. Specific learning disabilities are neurodevelopmental disorders that interfere with a person’s reading, writing, listening, mathematical, and reasoning faculties, according to the American Psychiatric Association and the Colorado Department of Education. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, common specific neurodevelopmental disorders include: – Dyslexia, characterized by reading difficulties; – Dyscalculia, characterized by problems in mathematical reasoning; – Dysgraphia, characterized by writing and spelling difficulties; and, – Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, characterized by frequent inattentiveness, hyperactivity, and impulsive behavior. Symptoms of these disabilities can co-occur in the same person, and past research points to stark racial disparities among those diagnosed with such learning disabilities, including ADHD. Data from the CDC between 2016 and 2018 showed that non-Hispanic Black children were more likely to be diagnosed with learning disabilities than their white and Hispanic counterparts. Non-Hispanic white children also demonstrated a greater likelihood of being diagnosed with learning disabilities than their Hispanic counterparts. Black students are then more likely to face disciplinary removal from class rather than treatment for behavior resulting from learning disorders. Because proper diagnosis across demographics is the first step for students to get the supports and services they need in school to be most successful, Marker Learning examined racial and ethnic differences in students with learning disabilities using data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Learning disabilities are most often diagnosed during adolescence Marker Learning Parents and caregivers often notice signs that their young children learn and understand things differently early on. It’s usually not until kids are school age, however, that they are diagnosed with learning disabilities. The academic demands of adolescence, which begins at about age 10, tend to widen the gap between academic expectations and academic achievement. Additionally, with age, parents become adept at separating symptoms of a possible disability from lack of effort, prompting a closer look. According to Johns Hopkins Medicine, the road to diagnosis often begins when parents or teachers notice children having trouble with reading, writing, or following directions. From there, school specialists work to suggest the appropriate testing and interventions to identify learning disabilties in students. Parents might also get private evaluations, outside of the school, for diagnosis. Black students are most likely to be diagnosed with a learning disability Marker Learning Black students are more likely to be identified as having a learning disability than other students. They are not only more likely to receive late-stage ADHD diagnoses, but are more likely to encounter systemic barriers, such as “disparities in the processes leading to a potential diagnosis,” according to a 2021 study in the journal Academic Pediatrics. Such barriers make obtaining the necessary support for overcoming disabilities a challenge in itself. Black students are also less likely to be identified as having speech impairments and autism, according to data by the U.S. Department of Education. These disparities in disability diagnosis might suggest a troubling pattern in the public education system. Studies show that the pervasive systemic racism in schools often lead to Black students being pipelined into special education at higher rates. They also show that income alone cannot explain the disparities in identification. Stereotyping children based on income or race can lead to misdiagnoses, as noted by the NCLD, leading to children being put in special education programs when they do not need those programs. Such inappropriate placement can have harmful short- and long-term effects on students from low-income families, including students of color from poor backgrounds. Family income and life experiences can significantly impact learning disability diagnoses Marker Learning According to the National Center for Learning Disabilities, children from households at or below the federal poverty level are more than twice as likely to have learning disabilities as those from households with income four times the poverty level. The link between poverty and learning disabilities is complex, but in general, such prolonged and often generational financial hardship is associated with increased adverse childhood experiences (ACES). Loss of a parent–which can be from life events such as divorce, separation, or incarceration–neighborhood violence, and experiencing racism are all ACES that can affect a child’s learning and behavior in the classroom. The Century Foundation reports that economic difficulties also affect children’s access to technology, limiting their access to tools to help overcome their disabilities. To make matters worse, school districts in poorer neighborhoods, which draw less in tax revenue, may, as a result, lack sufficient resources to ensure students with learning disabilities receive both the attention and access to the technology they need. White children with learning disabilities are more likely to have parents who didn’t go to college

Exploring racial and ethnic disparities in learning disability diagnosis among students